When the world turns black

danceGATHERING ignites the technology of collaboration in virtual space.

How do we dance together when our bodies are separated?

What if this end never ends? How does the world breathe again?

In the face of global shutdown, Zoom, YouTube and Instagram become new stages for performance. Late night television is filmed from home studios. Musicals are transitioned from stage to streaming. And bands are hosting concerts on front porches.

For many artists, collaborating on the stage—acting, dancing, playing and moving with each other—is special. Something distinctive arises from the gathering of people and live performance.

This was even more true for danceGATHERING, an event that—at its core—was built on the physical assembling of people.

Hosted by QDanceCenter Lagos, danceGATHERING is an annual performance lab and convention for creatives. Qudus Onikeku—the UF Center for Arts, Migration, and Entrepreneurship’s first Maker in Residence and co-founder and artistic director of QDance Center Lagos—calls danceGATHERING “anti-disciplinary.”

When you arrive in Lagos, Nigeria, Onikeku says you leave your discipline behind. Dancers don’t bring works. Scholars don’t bring books. Instead, people gather to meet each other and create something they couldn’t plan for.

“Sometimes we mistake ourselves for our disciplines,” Onikeku says. “People mistake us for what we do. But what we do isn’t what we are. All of us creators, we all are storytellers, only that we all are using different tools.”

Despite its name, dancers are not the only attendees at danceGATHERING. The festival invites artists, thinkers, administrators, technicians, dreamers, healers and more to spend one to two weeks in Lagos meeting and collaborating on something new.

“All the logic of your discipline doesn’t work here,” Onikeku says. “Whatever you come up with becomes the festival.”

Each year, danceGATHERING has a theme that spurs the creation of work, which culminates in street performances in Lagos.

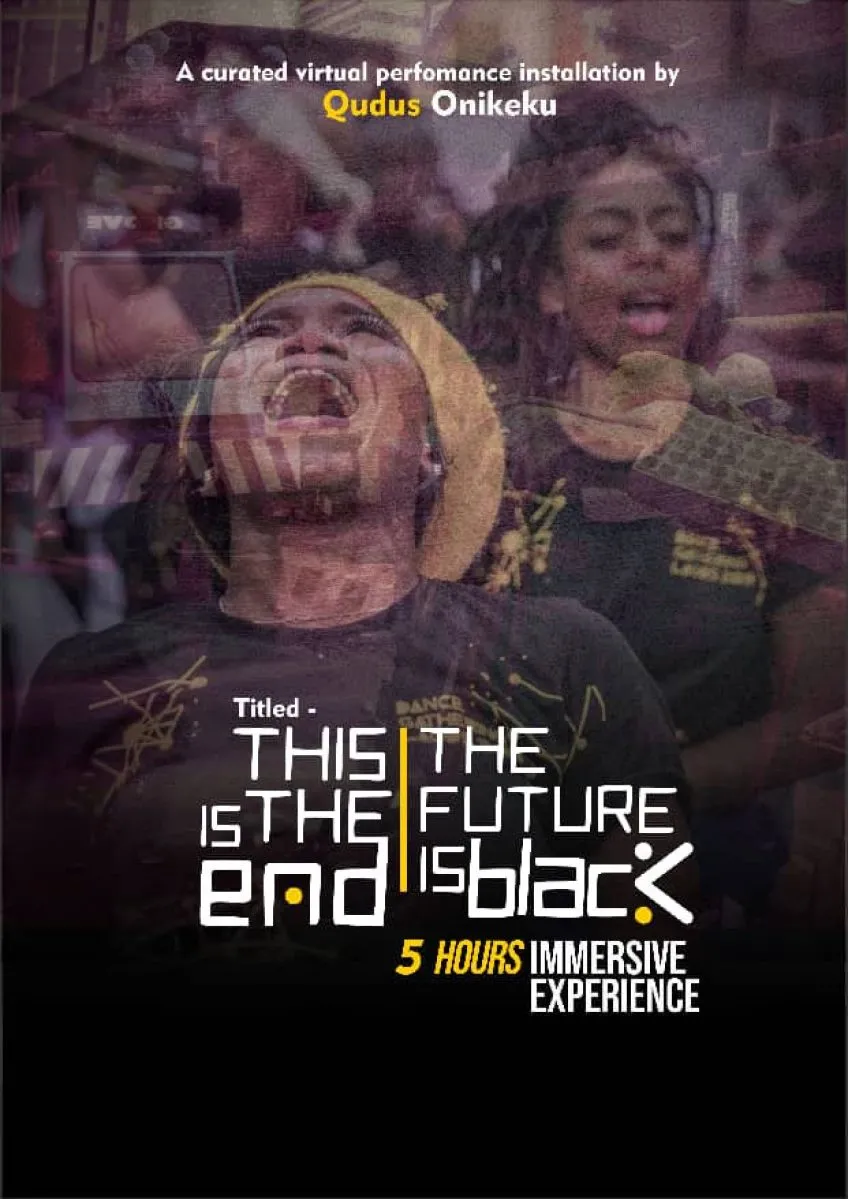

The 2020 theme was decided over a year ago: THIS IS THE END. THE FUTURE IS BLACK.

“We were already saying 2020 isn’t going to be like every year,” Onikeku says. “Looking at the world with a critical lens, we know something is going to threaten us. This was going to be a rehearsal space for the blackening world. Let’s gather and rehearse that future.”

When faced with the global pandemic, Onikeku and Hajarat Alli—research assistant for the Center for Arts, Migration, and Entrepreneurship and executive director of QDanceCenter—had to consider the fate of the 2020 festival, scheduled for April 18. With a theme intended to rehearse an unknown future, cancelling danceGATHERING wasn’t an option.

“We thought it would be stupid of us to cancel it,” Onikeku says. “The world became black. What if we all cannot move again? What if this never ends? What is going to happen to the art world?”

Transitioning danceGATHERING to a virtual space while maintaining its integrity had both technical and conceptual challenges.

But the concept of virtuality wasn’t entirely new to Onikeku or Alli, who are both native to Nigeria.

“Thinking from an African perspective, we have a different understanding of virtuality,” says Onikeku. “Anything not happening in a physical space is virtual. Dreams, visions, premonitions. This isn’t really about COVID-19. Our number one question is: What is virtuality?”

Only four weeks away from danceGATHERING, Onikeku and Alli rallied a group of participating artists to answer the question and create a virtual festival.

For three Saturdays, the group met on Zoom. The first week was spent meeting each other.

For the second, Onikeku and Alli randomly split up the group in multiple virtual breakout rooms. When they all came back together, each group presented ideas for what they wanted to create, and everyone was able to volunteer to join different projects.

“Every year, you make a new connection with someone,” Alli says. “During the Zoom sessions, there was a renewed feeling of doing something.”

The participants had about ten days to collaborate across the world to create videos that included rap, movement, and painting, among other creative forms.

Meanwhile, Alli faced a technical nightmare. Internet speeds and reliable connections are challenging in Lagos, and 45 people were about to send video footage to her all to be compiled and uploaded to a YouTube livestream.

Alli’s home internet connection wouldn’t cut it. She needed to reach a telecommunications company to upgrade, but as COVID-19 became more of a threat on her home front, even going to market to get food for her family was challenging.

She says police often stop her and ask where she is going. Without an essential excuse, you could get turned away and told to go home.

“It was like a real marathon,” Alli says.

She managed to secure adequate connectivity for her and Onikeku to host the live stream, but other festival participants in Lagos were still without reliable connection.

“Most of them are young,” Alli says. “We couldn’t just leave them on their own.”

Alli reached out to the partners and supporters of danceGATHERING to help, including Institut Français and Pro Helvetia Johannesburg.

Osubi Craig, the director of the Center for Arts, Migration, and Entrepreneurship, ensured that the center could send funds to help get everyone online.

In the end, the center and other partners provided internet modems and data for all of the participants to be able to attend the pre-meetings and so they could watch and engage in the main live stream event.

The 45 artists had until three days before the festival to return all of their products to Onikeku and Alli, who then had two days to stitch hours of content together, splicing it with narration and conversations, all while they held their breath that it would all upload in time.

On April 18, Onikeku and Alli launched their first YouTube live stream, dropping five straight hours of content, an event longer than most live-streamed productions, including sporting events and United States award shows.

Over 5,300 people tuned in from 40 countries, and after the YouTube live stream, over 50 people floated in and out of a Zoom after-party. A number of museums and festivals are already interested in showcasing the five-hour collection, according to Onikeku.

He and Alli agreed that simply moving the festival online wasn’t enough.

“The future is not about the tools,” Onikeku says. “That’s not the thing. The thing is in the collaboration that we want to have. Many people don’t know the technology of collaboration.”

Onikeku says it is critical to ask what a collapsed work and home environment looks like for artists. Always in the studios and on the roads, the concept of place can be important to the artistic process and shared space may be crucial to collaboration.

danceGATHERING 2020 proved virtuality is a space.

“We were one of the few on a global scale that were able to quickly adapt something of this magnitude without watering down the power that it carries,” Onikeku says. “It’s now becoming the basis of what we’re thinking about going forward. We can have this merging of space and time. Why not make the experience local and global at the same time?”

As the Center for Arts, Migration, and Entrepreneurship’s first Maker in Residence, rethinking and rehearsing the future of artistic practices is Onikeku’s job and determining how artistic practice and cultures migrate through virtual space is a question the center is positioned to answer.

“In this genesis moment for the center, Qudus Onikeku is the perfect and the only type of artist we need,” the center’s director Osubi Craig says. “Somebody that is going to bring a lot of people together. Somebody that responds to the world around him.”