Dancing in the Archives stages research-informed performance inside UF Libraries

Dancing in the Archives is an ongoing collaboration between the School of Theatre and Dance and the University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries Special Collections. Dance majors conduct archival research on three African American women who shaped the modern dance repertoire—Katherine Dunham, Zora Neale Hurston, and Pearl Primus—culminating in public performances in the library.

In the quiet stillness of the Judaica Suite, there is movement.

Movement through storage boxes and around tables of photographs. Incendiary movement that challenged the historic cultural moments they originated from. Powerful movement that permeated through the performers who embodied them. Movement that pushes against the boundaries that seek to confine it.

When most people consider what is kept in libraries and archives, dance is not the first thing that comes to mind. The very nature of dance is ephemeral, an experience shared between performer and audience until that moment is over. And for dance performances that occurred long before the days of phones and video recording, what is there to be remembered?

In Spring 2024, dance majors enrolled in the Dance History course taught by University of Florida School of Theatre and Dance (SOTD) professor, Rachel Carrico, PhD, researched, choreographed, and produced the fifth iteration of Dancing in the Archives.

The project is the result of an ongoing collaboration between the SOTD and University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries Special Collections that began in 2020 when Carrico arrived at UF. She devised the project alongside Literary Manuscripts Archivist, Florence Turcotte, and then-curator of the Belknap Performing Arts Collection, Jim Liversidge.

“Our dance majors choose their majors because they love to dance,” says Carrico. “They come to it from the practice, and they’re interested in the history. They want to learn, but they can certainly learn the history of dance without learning how to do archival research.”

And while dance majors—and students across many other majors and disciplines—may not have to go to the archives, Carrico sees tremendous value in her students making the trek from the Nadine McGuire Theatre and Dance Pavilion to the Smathers Special Collections, where they learn the ins-and-outs of conducting archival research with the help of library professionals like Turcotte and Liversidge.

“There is, I think, a shift from seeing something on a screen to appreciating its materiality. And there’s also very different parts of the brain that are activated in the exploratory process when you’re handling physical objects and opening folders versus scrolling down a vertical line of things that have been digitized. The kinds of connections they can make, I think, are possible because we’re there in person,” Carrico says.

From photographs to news articles to advertisements, students have their choice of objects in the UF Special Collections, so long as the object itself is a primary source. Students complete a research essay on their chosen object, and after learning their research interests, Carrico organizes her students into groups to choreograph performances based on the choreographers connected to their artifacts.

“I want to make [archival work] relevant to them and get them excited about it so they can see how it can deepen their own practice and their own creative process,” she explains.

Twentieth century African American choreographers Katherine Dunham, Pearl Primus, and Zora Neale Hurston, whose careers as dancers were profoundly impactful in the shaping of the modern dance repertoire, are the subjects at the forefront of the Dancing in the Archives project.

As African American women whose work is primarily situated in the pre-Civil Rights Era, the multi-hyphenate careers of Dunham, Hurston and Primus existed in the context of violence, racism and inequality against Black Americans. Despite having obtained international recognition during their careers, the hostile cultural climate extended into the canonization of dance, where their contributions would be overlooked for decades by white dance scholars.

“The archive is a place of power historically,” explains Carrico. “And the repertoire is a tool of subalterns throughout history to hold on to their histories when they’ve been stripped of their material records.”

The question of who is granted admission into the archives is also central to the discussion of the archives’ value.

As Carrico’s class made their way into UF Special Collections to begin their own research, they brought with them these important questions about the archives and what their role in them might be as dancers.

Bringing the archives to life

There to greet them outside of the Grand Reading Room were Turcotte and UF College of Liberal Arts & Sciences PhD candidate in English, Tiffany Pennamon.

“We’re in Florida, and we have these materials at our disposal,” says Carrico of the collection. “And Florence Turcotte is a wonderful archivist who works with the materials and is very willing to work with us.”

“The power of the archive centers around how histories are preserved and told, and whose are erased or forgotten,” Carrico notes. In a world that has consistently sought to diminish the accomplishments of Black women including Dunham, Primus, and Hurston, the availability of a collection reflecting their professional and artistic memory is an invaluable resource.

Turcotte has represented UF Libraries in the Dancing in the Archives project since its initial development in 2020. Liversidge, who oversaw the collection that houses UF’s dance and popular culture holdings, including the Dunham and Primus materials, also worked closely on the project until his retirement in 2023.

The first series of performances that were based off Dance History students’ archival research took place just ahead of the COVID-19 lockdown in one of the dance studios and were held without a public audience. And while 2021 was a blur of online and hybrid work, 2022 saw the Dancing in the Archives project come closer to its current iteration.

“All of our studios were booked,” Carrico recalls. “I thought well, you know, maybe necessity is the mother of invention. Let’s think of some interesting spaces.”

Although Carrico’s initial idea was to host the performances in the Architecture & Fine Arts Library, the 2022 performances ultimately took place in the breezeway connecting FAA and FAC.

“It was really cool because we used the glass corridor and the outdoor space below,” explains Carrico. “That’s when we started to play with what this could be like if we really took into account the architecture and corresponding layout of the space, and where audiences would be viewing from.”

Inspired by the ingenuity her students exercised in choreographing their performances in this unique setting, and with the support of Turcotte, Carrico sought to host the project in a space that would continue to foster innovation on the part of her students while also being conducive to hosting a broader public audience.

In 2023, Dancing in the Archives officially made its way inside a UF library, when Rebecca Jefferson, head of the Price Library of Judaica, suggested the Judaica Suite.

Located just off the Grand Reading Room, the two-floor Judaica Suite was designed by UF alumnus Kenneth Treister. With an abundance of alcoves, sculptures, lighting options, and other unique features, the Judaica Suite offered students an architecturally dynamic space for choreographing their performances.

“What I love about this space is that the limitations produce possibility,” says Carrico. “Because not all audience members can see everything all the time, the choreographers really work with that to explore themes of what is revealed to the public and what is withheld, or to play with perceptions of time, or understanding all components of a story.”

With its dual function as a classroom, the Judaica Suite provided the opportunity for students to research, choreograph, and perform in the very space where repertoires are archived and canonized. Rather than existing as a space apart from the performance, the archive itself became an active presence in the research process.

“Collections have research value, but only if you know what it’s all about—so, a lot of times, that’s what archivists do,” says Turcotte. “We chase down metadata about different items to get it in the hands of people who can make meaning from it.”

Once the dancers have the material in hand—and training from Turcotte how to handle it—”it’s like ‘wow, this archive is coming alive,’” Turcotte says.

“[Dancing in the Archives] brings movement to a static collection that ends up at the end of the day getting tucked back into folders and into boxes and put into a dark, cold place. Which is where that needs to be, because you don’t want the materials to be exposed to sunlight and warm air and moisture and humidity. You need to control all those aspects—but bringing them out and having the students interact with them, and then showing that in the dance is really an amazing phenomenon.”

Asserting the archives as a space for all

From their history of racial and gendered exclusion to their real and perceived associations with academic elitism, archival spaces often carry an ethos of exclusion; untouchability. There is a pervasive misconception that only those with experience in conducting archival research are welcome in them.

“You walk in the building, and you smell old paper,” says Turcotte. “It’s an acidic paper smell and some people love it—I’m one of them—but other people say ‘oh, it seems so antiseptic in here,’ or ‘it seems so scholarly,’ and they get intimidated.”

Dancing in the Archives, she says, provides an entry point for those who may be intimidated, or who may have previously perceived that the archive does not welcome their presence and participation.

“This type of event really welcomes people that may think of themselves as outsiders in the archive. It makes them feel like ‘oh, I could be part of this,’ or ‘I can have a part in this whole process, and learn from it and teach others,’” Turcotte says.

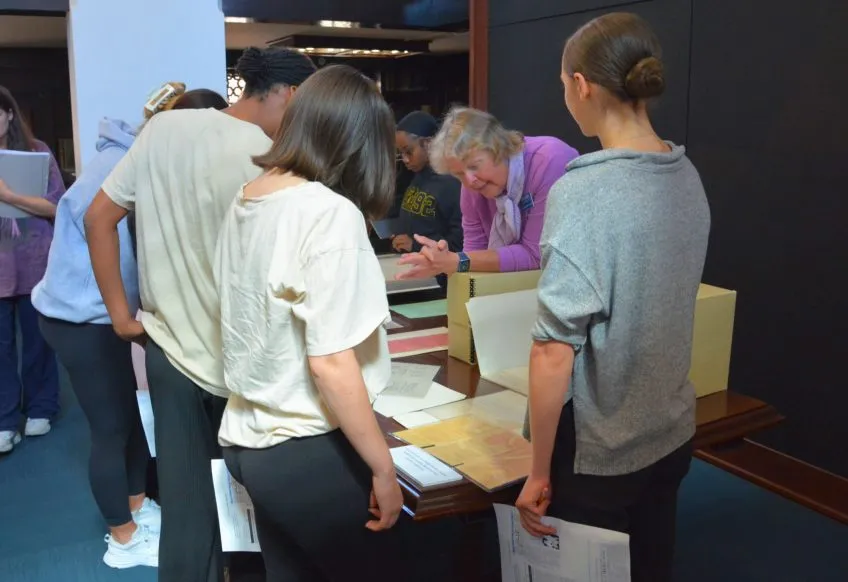

As the students’ point-person in the archives, Turcotte shares best practices for handling the archival materials and instructs the dancers on how to move safely through the Judaica Suite. She notes that her primary goal is to encourage the students to see the space as one meant to support their interests.

“The first thing we do is say ‘You are welcome here. This is your house; these are collections that the public has access to. We want you to use them.”

Turcotte says that one of the most rewarding outcomes of this project is seeing students make connections between what they are discovering in the archives and other courses they are taking.

“You get students coming in and saying ‘I could use this in my history class. I could use this in my English literature class. I could use this in my African American history class.’”

Largely consisting of photographs, promotional materials, and an assortment of personal papers, the archival collection in UF Libraries provides students with valuable resources to understand the choreographers as complete people. Huddled around study tables in the Judaica Suite, the dancers sort through photographs and records to see what the archive has can reveal about choreographers Katherine Dunham, Pearl Primus, and Zora Neale Hurston.

Fourth-year dual major in dance and construction management, Tamya Ruff, explains that “[Dunham, Primus, and Hurston] were just coming out of Jim Crow laws going into the Civil Rights Movement,” and notes that the body of work surrounding these dancers reflects both the highs and lows of the era.

Ruff’s research focused on the influence of Hurston in sharing Bahamian dance traditions in the United States as well as the erasure of the accomplishments of Hurston and Primus and many other Black and brown performers during this period.

Depictions of African American performers and their bodies were also at the center of dance major Rita Rodriguez’s paper, which compared two playbills advertising Katherine Dunham’s Tropical Revue. Both portray the dancer, but to very different effects.

“One just decided to use a black and white photo,” says Rodriguez, “the other one decided to use this illustrative design that was very cartoon-like. They distorted her body in a way that I have seen a lot of female bodies being distorted from that time.”

Preserving history to center Black joy

To explore these choreographers in the archive is to learn not only about the work they did, but also the way the world perceived their work. And no part of the collection embodies this sentiment as well as the Zora Neale Hurston collection.

“The foundation of this archive came from a very unhappy period of [Hurston’s] life,” explains Turcotte. “She was an unknown. Her books were out of print. She was a ward of Saint Lucie County, which means all of her care was taken over by the County.”

When Hurston passed away in 1960, she left behind piles of papers that social workers presumed were “junk.” Unaware of the decades of writing, activism, anthropological work, filmmaking, and choreography that came of her life, it did not cross the mind of anyone at the St. Lucie County Welfare Home, where Hurston spent her final days, to preserve her papers—or to even sell them.

Turcotte describes the story of how Hurston’s papers made their way to UF as an “archival superhero story” that began with the timely intervention of St. Lucie County’s first Black sheriff’s deputy, Patrick DuVal.

“The sheriff’s deputy, Patrick DuVal, was a friend of hers who just happened to be going by her residence when these materials were thrown into a burn barrel and lit on fire in January of 1960. He literally put a hose in the burn barrel and extinguished the flames,” Turcotte says.

“And the materials that were rescued … were brought to the home of a friend of Hurston’s, where they were dried off on her front porch. This person said, ‘they need to go to a research institution’ and she had them sent to the University of Florida, probably at her own expense.”

The poignant efforts of these “archival superheroes” underscore how meaningful it is that Hurston’s papers are accessible to students today.

“Hurston’s life was almost rubbed out of the historical record. What we’re doing, here, is preserving that record and celebrating her. It took 16 years for the rest of the world — [for] Alice Walker—to rediscover Hurston and bring her back to life, in that respect. And then it took another 20 years for us to get these materials digitized and preserved in these mylar containers and non-acidic folders and make them available to researchers,” Turcotte says.

“You can see the singe marks and students can turn those pages,” says Carrico of the rescued Hurston papers. “The goal is that they’re connecting the dots across history that the materials we have to write [about] history are only a small portion of what has existed in the world.”

“Hurston’s papers,” Carrico adds, “were put in a burn bin and set on fire—not because anyone was seeking to destroy her intellectual property, but because sexism and racism of the time determined that her intellectual property wasn’t valuable and therefore was disposable.”

It is this sharing of the archive and its contents that make the job especially rewarding for Turcotte: “Scholars come and research. Fans of Hurston and people who appreciate her work and her spirit get to hear the story. And the students [get to] relive this Black joy through their dancing,” she says.

From the relief of saving archival memory to seeing the technical prowess of Primus in photographs of the “gravity-defying” jumps for which she is known, the archives show the cultural leaps and bounds spearheaded by the three women and continued through researchers, archivists, choreographers, and everyone else who finds meaning in their work.

And the Dancing in the Archives project challenges students to consider how they as individuals might make use of the sources to which they have access to broaden the canon of dance themselves.

“I think [the archival research process] connects them to history in a much more immediate and physical way,” says Carrico. “And I like to think it would be true for anyone, but I feel like for dancers who are tactile, embodied, and used to sort of processing information in that sensory way, it really makes sense.”

After weeks of research and choreographing, the students in Carrico’s Spring 2024 Dance History course extended an invitation to the archives of their own—this time, to the public.

Come rain or shine… or more rain

The ephemerality of dance and performance was never more apparent than on the day of the Dancing in the Archive performance.

As the April 3rd performance date dawned, so did one of spring season’s first torrential downpours. Tweets and social media posts promoting the performance became intermixed with weather alerts for flash flooding and dangerous driving conditions.

Inside the Judaica Suite, the rain pattered on the roof and darkened the large windows of the room—a noticeable contrast to the light-filled afternoons Carrico’s class had previously rehearsed in. The violence of the day’s storm clashed with the stillness of the archive, inviting audiences to reconsider the space they stood in—and even showed how, despite its historically exclusive nature, the archive could become shelter.

Audiences first arrived at the mezzanine. The dancers then directed visitors toward different rooms and vantage points with each performance, allowing the audience to experience their own element of choreographed movement as they were guided through the space. Carrico unpacks the process the students went through in translating their archival research into dance performances:

“One of the questions that they have to be accountable to when they’re in their creative process is: what movement vocabulary do you choose? And why? And by movement, vocabulary, I mean the world of your choreography … is it based in a kind of Africanist sensibility? Or is it very sort of white U.S. Postmodern? Or is it very balletic? And all of those choices are valid — they just have to be able to explain why, and not default to something because it’s what they know.”

Carrico further explains that the movement vocabulary the students choose depends on who they focus on in their research.

“There are things in the Dunham technique that we really identify and talk about that show up in their performances. For example, she has a very specific placement of the way the arms are held; the way the torso contracts, the undulation of the spine. We talk about how her technique comes from her ethnographic research in the Caribbean and particularly that spine undulation from the dance for Damballa and Haitian vodou. And so, you’ll see some of these very specific things, especially in the Dunham pieces,” Carrico says.

She adds that, “in the Primus pieces, you’ll also see some of that. The Africanist sensibilities — the body really grounded, the knees bent, the feet flat. The torso kind of angled to the ground, and articulation of the spine. All of these things that have been identified by many different scholars of characteristic of multiple dances either in Africa or in the diaspora that have African roots.”

Carrico recalls the unique way dancers in the 2023 Dancing in the Archives performance paid homage to Primus’s signature leaps:

“It’s really hard to do these leaps — even if you can, physically — in that space,” she says. “One group made the choice to take this image of her air-bound in one of those leaps but [to instead] lay it on the ground. They laid their bodies flat on the ground in the position of one of these leaps, and then the audience was above and could look down and see that physicality.”

Ruff explains how Hurston’s research on migrant workers, and the songs and dances the workers devised and shared, influenced the 2024 Dancing in the Archives performance.

“They would make up these songs and these dances that would keep their minds off of the hard lives that they were living at the time, so that’s what we were trying to embody in our dance,” Ruff says.

Among these dances was the Crow Dance. Because no videos exist showing Hurston performing the dance, the group had to get creative in figuring out how to interpret it.

“They only had pictures of the Crow Dance. But we looked at a video of a theatre company, Bread and Puppet Theatre, who had recreated it, and they used the audio of Hurston’s voice talking about it and singing it,” Carrico says.

Using movements grounded in Africanist sensibilities, the group embodied the characteristics of a bird to evoke the Crow Dance.

“They’re able to do that,” Carrico notes, “because our curriculum requires them to take African diaspora dance in equal measure with ballet and contemporary dance from their first semester.”

Beyond the movements themselves, several of the pieces drew from the anthropological work and research that the three choreographers conducted during their lives.

Dance History student, Vanessa Rood, explains that her group’s performance was meant to reflect Dunham’s travels abroad and the sharing of techniques that she learned. Making use of the Judaica Suite’s obstructed views and mirrored alcoves, the dancers structured the performance so that audiences on either side of the mezzanine would see only two dancers at a time, who would join the other two dancers in the center of the room before moving to the opposite alcove.

Drawing from a Dunham technique workshop, the group embodied how the preservation of dance memory has existed both inside and outside of the archive.

“It was an amazing synthesis of the readings and the research papers that they had to write,” says Turcotte of the performances. “Seeing what the students did with the materials that they studied was so gratifying and very much different from what we would consider ‘dry’ archives research. That’s why we’ve invested so much in the collections’ care—the air conditioning, the storage, the enclosures, these different archival materials. This is why it’s worth the money that we invest in it: because of its research value.”

Carrico notes that she is consistently impressed by the caliber of her students’ work in Dancing in the Archives projects, given the limited time frame they are given.

“I wish this could be a whole semester class, and this would be all we do, but I [have to] wedge it into Dance History. I don’t give them much time, but they never complain—and they crank out really phenomenal work,” she says.

For Rood, spending time in the archives poring over Katherine Dunham’s archival materials was a unique and invaluable experience. “I feel like in this experience of coming to the archive … there’s a level of reverence that happens with that exchange of physical property, and then being able to contribute something ourselves,” Rood says.

Ruff, whose research and performance centered on Hurston’s anthropological work in the Caribbean and the Crow Dance, says she plans to continue her study of Bahamian dance techniques outside the Dance History course.

By partnering with UF Libraries, and archivists like Turcotte who lovingly maintain them, Carrico’s Dance History class invites audiences in to show that archives are meant for everyone. And it is through the participation of everyone—be they professors, librarians, archivists, students, dancers, or just everyday people who enjoy a good dance performance—that the archives continue to be an important resource in preserving our histories.

“The librarians that work in this building really enjoy it,” says Turcotte. “It’s become a tradition that we want to uphold.”