Black Futures: Black artists and scholars reclaiming histories and reframing futures through the lens of joy

Porchia Moore, Ph.D, remembers the moment she recognized museums in the U.S. were at a crisis point in their ability to access a generation of Black visitors.

Moore, an activist-scholar and curator, is Department Head and Assistant Professor of Museum Studies at the UF College of the Arts School of Art + Art History. She combines a datalogical background in library science with an intersectional “museum visionary” approach to developing inclusive cultural heritage spaces. Moore co-founded the Visitors of Color project — an intersectional guide to resistance in museum spaces — with partner, nikhil trivedi, in 2015, in response to this moment:

Moore recalls surveying a group of undergraduate students at an HBCU and learning that none had visited the museums in their city — nor did they plan to, they told her, because they had no desire to subject themselves to institutional narratives that frame Black history as solely anchored to suffering.

“Ever since then, I have been thinking about the museum experience and how to navigate trauma — not just for visitors, but for museum professionals who are engaged by cultural heritage, cultural artifacts and material culture, and who are working to not just tell a single story, but to tell a multitude of stories — and to make sure those stories reflect historical accuracy, but also have a bent toward social justice,” Moore says.

She pinpoints Beyoncé’s Lemonade in 2016, followed by Solange’s A Seat at the Table in 2017 as praxis-shifting: the Knowles sisters’ canon-shattering works, which center Black womanhood in the American South, were accompanied by a groundswell of resources like Candice Benbow’s “Lemonade Syllabus” — a digital document Moore notes initiated a “shift in thinking about how people learn; how people disseminate information.”

Unfolding in concurrence with events rooted in racially motivated violence, such as the Emanuel AME church shooting in 2015 and the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally in 2017, Moore notes: works like Lemonade and their accompanying syllabi offer accessible windows, both artistic and scholarly, into a multitudinous Black history. They insist on a telling of history that is anchored not simply by the violence perpetrated against Blackness, but in the indomitable spirit of resistance and joy that illuminates the past, present, and Black futures.

In the Harn’s Shadow to Substance, joy tethers the arc of Black history

“In the last two years alone, particularly with the fact that so many museums had written statements about Black Lives Matter in response to [the murders of] Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd, it has been increasingly important for museum professionals to not only to talk about how to navigate these really important issues, but also talk about: what does it mean to be continuously confronted with Black death, Black grief, and institutional, systemic racism in public places?” Moore says.

Moore curated the Harn Museum of Art exhibition, Shadow to Substance, in collaboration with Kimberly Williams, University of Florida Graduate Candidate in English; and Dr. Carol McCusker, Harn Curator of Photography. The exhibition ran July 27, 2021 – February 27, 2022.

“One of my soapboxes is that ‘Black history is American history,'” Moore says.

“A thing I get frustrated about is that, somehow, when violence is predicated upon Black communities or Black people, it’s viewed with sympathy and remorse given to Black people only — as if this is not the responsibility and the pain and the grief of everyone as a collective; as Americans. It’s not solely Black death and Black grief, but it is truly the problem that needs to be solved by everyone.”

Shadow to Substance explores Florida history, starting with Jim Crow and the Great Migration and moving through the Civil Rights and Black Lives Matter movements, “through images that expand ideas around healing, myth, intimacy, joy, resistance and rebirth.” It was accompanied by a Spotify playlist and “Aftercare” reading and resource list developed by Moore and Williams.

“There are intentional places of respite, both visual and physical, in the exhibition space so that visitors could have the opportunity to sit down and read, think, and contemplate big ideas — and contemplate the emotional landscape,” Moore says.

“We had images that immediately call to mind Trayvon Martin; images that were triggering and traumatizing. We wanted to make sure that [the exhibition] spoke to all the different histories and violence, but that we were being ethical and responsible — and that we weren’t asking people to show up and interact with these photographs, and then leaving them to their own devices.”

Shadow to Substance, Moore says, derives its title from the abolitionist Sojourner Truth, who in 1864 began copyrighting her own image and selling carte de visite portraits with the inscription, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance,” for 25 cents apiece. Truth used the proceeds from her portrait sales to fund her own work and to support abolitionist and suffrage movements. She was among the most photographed individuals of her time.

“Sojourner Truth was born enslaved and took control of her image as a Black woman, which is in itself an amazing thing. By taking control — to the point she is the first person to actually copyright her images — she is taking control and agency back over her own body, and, by extension, the image of Black folks. What she did is say, ‘I want people to see me; to see my humanity, and to see me as a Black woman,'” Moore says.

“She was funding abolition movements and women’s suffrage movements — truly, she was funding the early Civil Rights Movement — with her photograph. That’s what the exhibition is speaking to: this one woman’s understanding that her photograph has that much power.”

Contemporary Black theatre sets the stage for reconciliation

Ryan Hope Travis, School of Theatre + Dance Assistant Professor in acting and performance, aims to upend the trauma narrative — which, much like its pervasiveness in museum settings, also exists in the dominant theatre canon. Travis devised and directed the play, New Berry, in 2021 to honor the six victims of the 1916 Newberry lynching, and to utilize the Hippodrome Theatre stage as a space for reconciliation.

“Generally, when a Black body is depicted on stage it is filtered through the lens of trauma. That mere fact makes anything in opposition to that an act of resistance. Therefore, joy becomes a palatable, tangible, expression of resistance,” Travis says.

“When we think about Black futures in theater spaces, what we’re really talking about is how we take our stories back; how we retell them, re-imagine them, and then present them with the most grace.”

Travis says his approach to devising Black theatre centers the question he often asks himself: “Where do I pull Black joy from?” He first leans into historical research to learn about the spaces his subjects inhabited, in time and geography, and then asks:

“Where are the jokes being cracked? Are they happening at the juke joint? At a prayer meeting? What could they be potentially gossiping about? It’s not a far leap to see what issues stir us today, because in the human experience, we have just a handful of stories: love, triumph, forgiveness … it comes down to: how do we approach that story, and from what lens do we come to action?”

In New Berry, Travis focuses on his subjects’ lives during the days leading up to their deaths, rather than on the act of violence committed against them.

“Often, a person’s life is reduced to the harm that was imposed on their bodies and in the last few moments of their life. What we lose is all the other intricacies that make that person a fully complex, vibrant human. As artists — if we can find a way to highlight all of the joy and positivity and dreams and ambitions that person had in their lifetime, then the act that was done and the trauma that was imposed becomes Ground Zero for something else. If we can highlight the person’s humanity, that alone makes the act of violence Ground Zero to mobilize,” Travis says.

Sojourner Truth, Beyoncé and Beyond: Black artists, innovators are Black Future

Travis sent his Acting for the Camera students to the Harn to create a work in response to what they saw in Shadow to Substance.

“When I heard of the exhibit, I wanted to find a tangible way for students to interact with it. A museum experience is deeply personal. When you can move from a singularly individual experience to something that is even more visible — that was the intention,” Travis says.

Haley Johnson, a third-year graduate student working toward her Master of Fine Arts in Acting, says two images from Shadow to Substance have stayed with her since her visit.

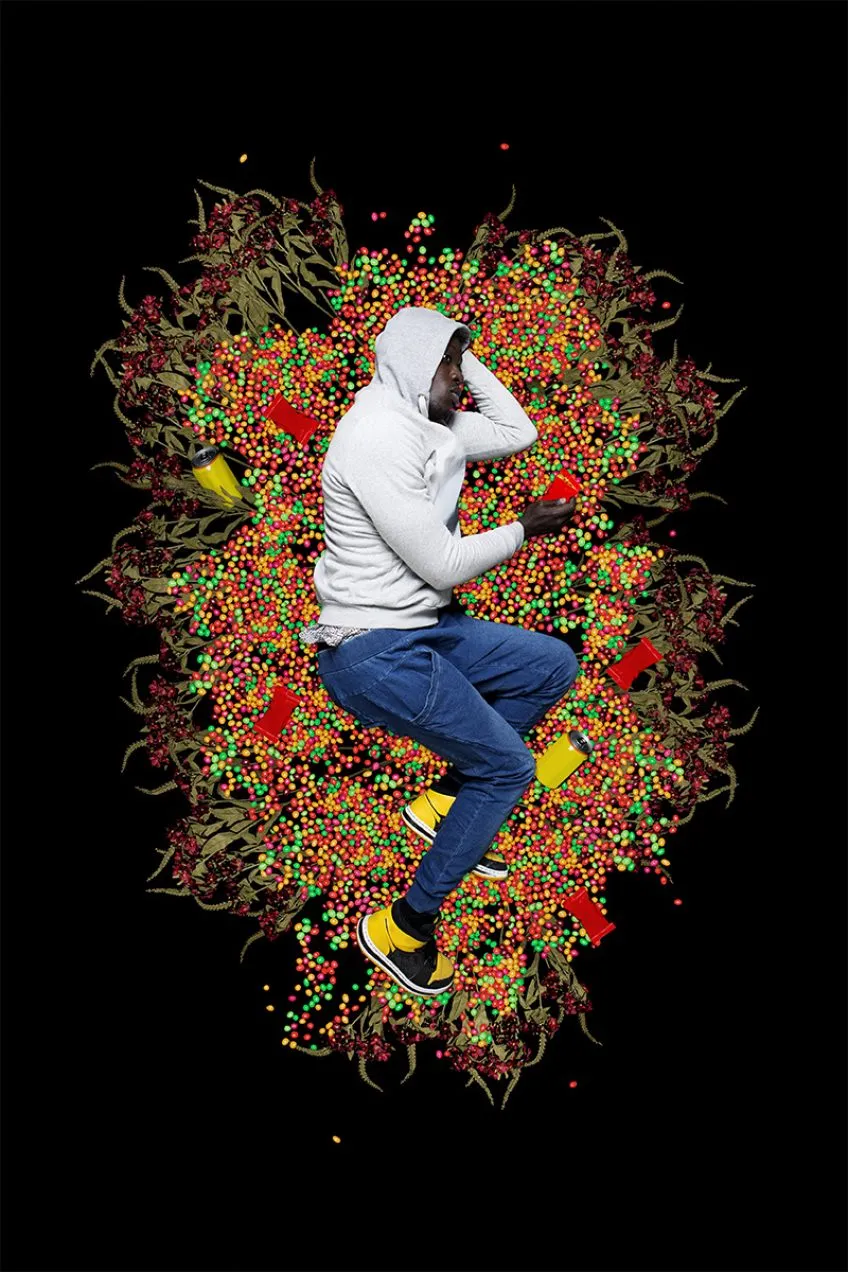

One is Omar Victor Diop’s allegorical portrait in which he plays the role of a young Trayvon Martin. The artist is photographed in gentle repose, wearing a gray hoodie, surrounded by a colorful explosion of Skittles. In his hand, a red candy wrapper.

“The subject appeared to be falling into an abyss, almost — and when I looked closer, it was actually the Skittles that he had; that he was walking with. I found that so striking,” Johnson says. She describes the image as “something beautiful; almost angelic.”

Johnson also notes, “one thing that really stuck out to me was how vital, and how viscerally they captured the Black experience — spanning decades and decades and decades.”

In Ayana V. Jackson’s Moments of Sweet Reprieve, from the series Intimate Justice in the Stolen Moment (2017), the artist duplicates her own image as two women dressed in 19th century period clothing, seated on a couch in a moment of rest; sororal intimacy. The calmness of the image recalls themes present in Tricia Hersey’s The Nap Ministry | Rest is Resistance project, also featured in Shadow to Substance.

“That was also extremely striking to me — just the placement of these Black bodies in places we don’t usually see them, and not so much in oppression,” Johnson says. “It was still showing our history, but some portraits, such as Moments of Sweet Reprieve, told our story in a different light — instead of being rooted in oppression — in a way that I really appreciate.”

Johnson says she’s currently “dipping her toes” into a genre-bending work set in the Baroque period and scored by Black music from the 1970s. When she considers her own future as an artist, she says:

“I just want to be a creative force in this field. I want to have the agency to produce my own work and have it make a difference; have it speak to somebody — whether that’s acting in a particular story where we’re not used to seeing a Black woman, whether that’s writing something that subverts expectations and really embodies a unique representation, or whether that’s directing. Whatever I do, I know I’m going to be successful and I know I want to have representation.”

“What [Ryan Hope Travis’] class really taught me,” Johnson adds, “is to be your own agent of creativity and to produce the work that you want to see; to show up in the room — and to know that you belong in every room you are a part of.”

When she considers Black futures, Johnson is inspired by contemporary innovators in the performing and visual arts like Issa Rae, Jordan Peele, and Kehinde Wiley.

“Black futures. Just those two words together is so aspirational,” Johnson muses.

“The idea of Black futures, especially in art and film, is very exciting because it’s going to be innovative, it’s going to be new, and most importantly it’s going to be needed. People are yearning to see not just Black people, but people of all sorts being placed in certain themes and situations and genres that we’re not used to seeing. It creates more of a dialogue. It creates more artists. It creates a whole other perspective in entertainment and art.”

Featured Image Caption: Ayana V. Jackson, Moments of Sweet Reprieve, from the series Intimate Justice in the Stolen Moment, 2017, archival pigment print, Museum purchase, funds provided by the David A. Cofrin Acquisition Endowment. On view in Shadow to Substance (July 27, 2021 – February 27, 2022) at the Harn Museum of Art.