Art history professor critiques lingering sexism in the contemporary art world

Rachel Silveri publishes essay on contemporary sculptor Arlene Shechet.

The recognition of modern and contemporary art has widely been dominated by men, most notably Auguste Rodin, Pablo Picasso, and Marcel Duchamp, to name a few. Assistant Professor of Art History Rachel Silveri, Ph.D., aims to challenge that in her recent essay about contemporary sculptor Arlene Shechet, titled “Arlene Shechet: History Matters.”

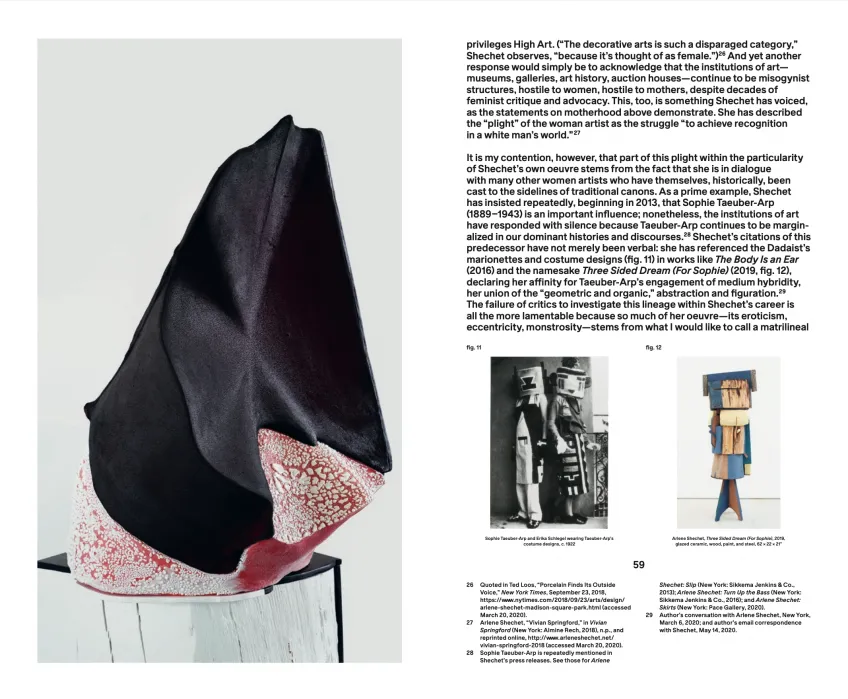

Silveri analyzes Shechet’s work from her show Skirts (2020) that was on display at the Pace Gallery in New York City, along other notable works throughout her career.

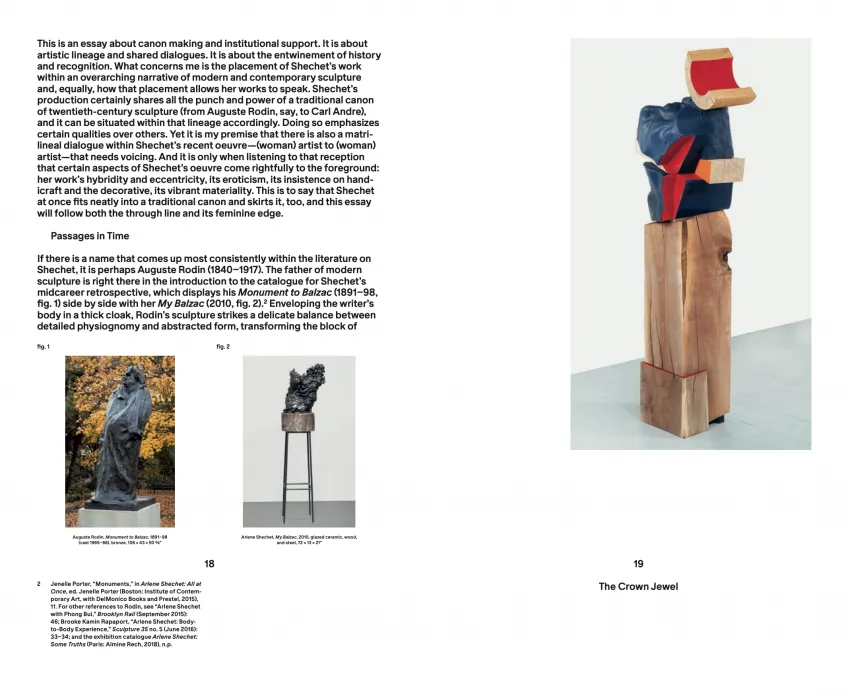

Silveri’s essay frames Shechet’s work within the broader history of modern and contemporary sculpture, noting that Shechet—who was born in 1951—has been working in dialogue with male “master sculptors” of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

“I wanted the essay to do three things,” Silveri says in an interview. “First, I wanted to situate her work within a broader history of sculpture, modern sculpture, and art historical writings on sculpture.”

Knowing that Shechet’s work fits within the frameworks of her male counterparts, Silveri asks why Shechet doesn’t appear in more art history texts and museum collection displays, calling attention to the lingering sexism that persisted, and continues to persist, within the contemporary art world.

Silveri explains that Shechet works in dialogue with male artists like Constantin Brancusi and Pablo Picasso, but she also argues that Shechet’s oeuvre, or body of work, exists within a “matrilineal dialogue” with an earlier generation of women artists like Louise Bourgeois and Dorothea Tanning.

Silveri’s writing of the essay coincided with teaching a graduate seminar, Feminist Art Histories, where Silveri explores the canonical feminine methodological concerns within art history and art making. She focused the most prominent issues on representation and craft.

Within the art world, fine art and craft are divided. The former is typically perceived as a “higher” form, serving no functional purpose but instead evoking intellectual thought or conversation. In contrast, craft is seen as “lower” and may serve a functional purpose, like textiles and ceramics. Silveri argues that Shechet’s work breaks this binary through her experimentation with ceramics and porcelain.

“Moreover, what does it mean to use materials in a way that might open out onto feminist questions or a feminist view of materialism, even if we can’t read a ‘woman’s body’ or the representation of a woman within the work?” Silveri says. “This is a question that goes beyond an engagement with craft or with certain feminized materials, and I think that that is a very relevant concern for contemporary production today.”

Shechet’s sculptural work experiments with different materials, including ceramics, wood, and metal.

“In Shechet’s work, surfaces change,” Silveri says in the essay. “That which is hidden becomes revealed. Something seen becomes something else. A viewer may have to stand on tiptoe and look up, or bend knees and lower her eyes to the base to witness the work’s transformative effects.”

As she works in dialogue with these great women artists of the not-so-distant past, while incorporating her own unique perspective regarding representations of women, materiality, and the binary of “high” and “low” art, Silveri argues it becomes more evident that Shechet deserves a place within the canon of contemporary art historical discourse and feminist art history.

Silveri’s active research is key to informing her syllabi in art history classes she teaches at the School of Art and Art History. She often adjusts and modifies course topics for the various classes she teaches to offer new artists and perspectives for her students to consider.

“I want art history to feel important to my students, to feel relevant to my students,” she says, “and it’s not going to feel like that by using one traditional textbook.”